We are pausing on our in-person sangha option at this time. Please join us on Zoom by clicking button above.

Need Zoom tech support to join us? Email Phyllis here.

(support available before sangha starts)

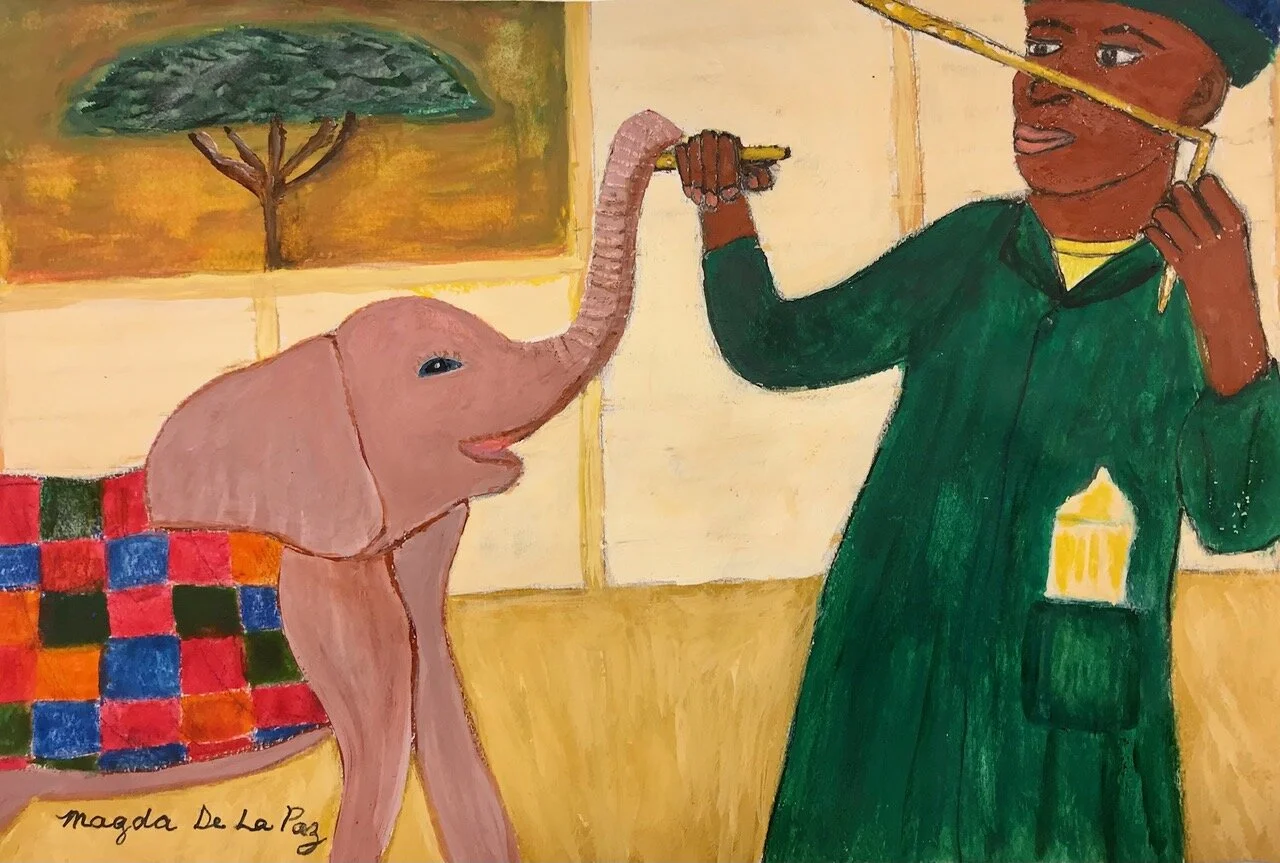

Magda will facilitate at our online sangha.

Magda shares:

“Acquire inward peace, and a multitude around you will find their salvation.”

Saint Seraphim of Serov

One of my favorite sentences in our sangha’s new Engaged Mindfulness Vision Statement is “Mindfulness is the awareness and transformation of not only our own suffering, but of the suffering around us.” This summarizes what engaged mindfulness means to me as well as the efforts of our Engaged Mindfulness Working Group to expand the mindfulness possibilities of our sangha. In the month of October, which our sangha is dedicating to engaged mindfulness, I am grateful that I feel ready to reach out and share the peace that I derive from my mindfulness practice.

In a month that is also dedicated to National Domestic Violence Awareness, I have decided to support Community Family Life Services (CFLS). CFLS assists formerly incarcerated women and their families, many of whom have suffered different forms of abuse. I would like to explain why I have chosen to support this organization by describing the connection I perceive between engaged mindfulness and the interbeing among all living creatures. I will focus in particular on the lessons I have learned from elephants.

THE CATASTROPHIC EFFECTS OF LOSING A MOTHER

“The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.”

African Proverb

My deep admiration for the qualities of elephants, and what they share with the best qualities in humans, ironically began when I first learned about their destructive tendencies. In My Elephants and My People, by Ugandan author Eve Abe, I learned how catastrophic the loss of a mother can be for a calf, an experience that Abe compared to those of war orphans. Reading about this called to mind the traumatic experiences of countless children whose family lives are severely disrupted, such as the children of incarcerated mothers.

HOW ELEPHANTS ARE THE BEST VERSIONS OF HUMANS

“Elephants are, indeed, like us, and in many ways, better.”

Love, Life and Elephants by Madame Daphne Sheldrick

My admiration for elephants has inspired me to read a great deal about them and to eventually sponsor two female orphans: Malima, who is now five years-old, and Larro, who is four. Two years ago I visited Kenya to observe elephants in their natural environment. I also met Larro and one of her caretakers at the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Nairobi. While there are many qualities I admire in elephants, I will focus on those that relate to my decision to support CFLS.

Elephants are known to communicate in many ways, from physical gestures to trumpeting or low frequency communication that can span miles. I am delighted by the way that elephants trumpet when a new calf is born in their herd. Mothers are not only extremely affectionate towards their calves but make a variety of sounds to communicate with them. When a male adolescent starts venturing away from the herd, he is still within his herd’s field of communication.

I believe that elephants can be described as contemplative in the way they value and mourn their dead, silently remaining next to the body for days. “Nowhere to go, nothing to do,” as Thich Nhat Hanh would say.

Mothers develop close bonds as they help each other raise their calves. They do justice to the “It takes a village” proverb. This strong social and family infrastructure helps calves grow into emotionally stable and well-socialized adults. I remember watching a matriarch disciplining a calf who was jumping on top of another. I suppose she was teaching the calf not to be a bully.

Like human children, calves’ brains take a long time to develop in a nest nurtured by the steady presence of caring adults. Attachment, belonging and safety are essential. Exclusion is the worst kind of punishment.

Elephants are repositories of knowledge. They never forget the elephants and humans who love them. Neither do they forget those who hurt them. In Africa, they know which tribes to trust and which to fear. As with humans, trauma marks them for life.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF LOSING THE NEST

British soldier and elephant expert Billy Williams, who worked with elephants in Burma, explained that the bond between an elephant and her calf lasts a lifetime. “Separating such bonded elephants,” he noted, “is indeed cruel” (Elephant Company by V. C. Croke). Williams secured changes in the conditions for working elephant mothers as seventy percent of their calves died for lack of constant maternal protection.

In a similar vein, I believe that among the most tragic things that can happen to a child is the loss of a mother to incarceration. While I believe that children are full of promise and capable of transcending the direst circumstances, research shows that children whose parents are incarcerated are at high risk for antisocial behaviors and psychological problems. These children often belong to traditionally marginalized groups and are regarded and treated as “other people’s children,” exacerbating their misfortunes. Punitive and discriminatory systems, inadequate resources, and absent role models can all contribute to problem behaviors as children grow up.

At a recent CFLS conference I learned that few people in the legal system ever try to find out about the life circumstances that can put women on a path to incarceration. One of the reasons I am inclined to support formerly incarcerated women is the transformative experience I had with a student when I served as dean of students at a high school. Her story reminds me of many of the stories I heard at the CFLS conference.

I met my student when I supervised lunch detention, after which she visited me regularly. After her father was murdered, I invited her to spend more time in my office.

This young lady had a violent streak which usually manifested with males. She perpetrated a violent attack against her stepfather, who was abusive toward her mother. One day during in-school-suspension, in a room full of male student offenders, it took the supervisor about two minutes of her presence to call security to remove her. Soon after this episode, she was incarcerated. It was in prison that she finally spoke to a therapist about the prolonged sexual abuse she endured as a child at the hands of her babysitter’s son. I was the second person to hear her story, soon after her release. She wrote me a letter assuring me that she would graduate for her mother and me, which she did. Her story made me realize why we need to learn more about incarcerated women’s lives and backgrounds. CFLS has a Speakers Bureau which trains formerly incarcerated women to speak about their experiences, helping them heal and heal others while being financially compensated. This is another reason I admire this organization.

THE ILLUSION OF SEPARATENESS

“Most sociopolitical hierarchies lack a logical or biological basis - they are nothing but the perpetuation of chance events supported by myths.”

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari

According to Thich Nhat Hanh, inferiority and superiority complexes develop when we lack awareness of the interbeing among all living creatures. When we view the world through the distorting lens of separateness, too much of our vocabulary can reinforce division and inequality.

I looked up the definition of the word ’rogue‘. For animals it means “an elephant or other large wild animal driven away or living apart from the herd and having savage or destructive tendencies.” For humans it is defined in male terms: “a dishonest or unprincipled man.” I found at least 50 synonyms for the term. I wish we spent more energy on preventive measures than on labeling and judging.

Do we naturally fear or feel repulsed by certain ‘outsiders’? In Sapiens, Harari suggests that we are biologically wired to feel repulsion towards what we believe is not clean, out of a fear of contamination. What happens when we are socialized into believing that certain groups are not clean? Harari explains that figments of the imagination - myths - often end up becoming very real and very cruel socially stigmatizing structures.

Society’s injustice towards certain socioeconomic groups often starts from one chance event in history. For example, when the Indo-Aryans arrived in India, they feared of being overpowered by an overwhelming Indian majority. They thus fostered the myth of caste, which eventually became an important part of the Hindu religion. Perhaps this myth was also the reason lighter-colored elephants were often considered superior, as discussed in The Elephant Lore of the Hindus by Franklin Edgerton.

A chance event that helped create the myth of white supremacy in American society was the advent of the transatlantic slave trade. In order for one group of people to profitably exploit another group, it fostered inferiority myths about the exploited group. These illusions of separateness were upheld by government officials, academics and religious leaders.

Unlike elephants, who trust their herds, rhinos have a deep distrust of other rhinos as well as other species. When I was in Nepal, I accidentally stood too close to a mother rhino and her calf; local people shouted that I had to run away as fast as I could. On the other hand, in Amboseli, an elephant sanctuary in Kenya, our jeeps were sometimes parked within a few feet of entire elephant herds. I was in awe.

Are we more like elephants or like rhinos when it comes to our own species? Do we have the luxury to trust only when we have certain degree of social and cultural capital? For me a very important work of literature on the effects of poverty on children is the Spanish medieval picaresque novel Lazarillo de Tormes. Lacking money, Lazarillo’s mother hands him to a mean-spirited blind man to serve as his guide. The first thing the man does is to trick him into getting hurt so that he will not trust humans again. This lesson serves him well since, from that experience on, each master is worse and more exploitative than the last. Early in his life Lazarillo is socialized into understanding his vulnerable condition and low place in society, a situation rooted ultimately in myths of inferiority and superiority. He understands his identity as that of a second class citizen, something akin to an untouchable.

INCARCERATED MOTHERS

Madame Daphne Sheldrick in Love, Life & Elephants is inspired by the plight of wild elephant matriarchs who stoically face the challenges of their long and difficult lives. The Amboseli matriarchs’ perfect control of their herds, who walked in well-organized lines behind them, was quite a sight for me. What would happen to the herd if the matriarch disappeared?

I feel the same way about the plight of incarcerated women whose lives have been filled with adversity. While it is well known that women face oppression in most societies, the experiences of traditionally marginalized women like the incarcerated are often especially harsh. They have often been sexualized and treated as adults much earlier than is natural, and are perceived as having a higher threshold for feeling pain, such as the pain caused by losing a child. Their children, ’other people’s children,’ are often not viewed as fully human. This is frequently an echo of incarcerated women’s own youths; many of these women were ‘other people’s children,’ too, and experienced immense adversity when growing up.

INTERBEING

How much can we expand our understanding of the concept of interbeing with those human beings whose life experiences have been quite different from ours?

The Buddha demonstrated his belief in the interbeing between social classes when he chose rural, untouchable children as the first people to instruct in The Way. It was as though he was greeting these outsiders with one of my favorite of Thay’s phrases: “A lotus for you, a Buddha to be.” When untouchable orphan Svasti turned 18 years-old, the Buddha returned to his village to invite him to join his community of interbeing. The Buddha believed that all children have the capacity for enlightenment and that they are “our children” no matter how marginalized their ancestors.

CFLS AND MEMORIAL FOR DOMESTIC VIOLENCE VICTIMS

When I think of certain passages in our new Engaged Mindfulness Vision Statement, I am strengthened in my desire to support incarcerated women like those who are assisted by CFLS. The concept of interbeing, as well as such lines as “Once there is seeing, there must be acting,” and “Mindfulness must be engaged,” inspire me to expand my own expression of interbeing by supporting those whose experiences are very different from mine.

The first effort coordinated by the Engaged Mindfulness Working Group to support CFLS will be a Memorial for Domestic Violence Victims: Healing Through Mindfulness with CFLS & Opening Heart Mindfulness. At this event, members of OHMC and CFLS will share some of their mindfulness practices. The ceremony will take place on Wednesday, October 27 between 1:00-2:00 pm via Zoom. Please email Magda Cabrero at magdacabrero@yahoo.com no later than Monday, October 25 if you are planning to attend. If you plan to bring family members and friends, please send their names and emails to Magda as well.

FOR A DESCRIPTION OF COMMUNITY FAMILY LIFE SERVICES: CFLS DESCRIPTION

FOR WAYS TO SUPPORT COMMUNITY FAMILY LIFE SERVICES INDIVIDUALLY OR COLLECTIVELY: CFLS WAYS TO SUPPORT

ENGAGED MINDFULNESS VISION STATEMENT: EMVS

Please feel free to speak to anyone in our Engaged Mindfulness Working Group. Our members are Adriana Arizpe, Camille Martone, Geraldine Canty, Magda Cabrero, Marie Sheppard and Phyllis Sandler. If you would like to join our working group please let me know in person or email me: magdacabrero@yahoo.com.

For Dharma Sharing, feel free to discuss your reactions to any of the following lines from OHMC’s Engaged Mindfulness Vision Statement:

“Once there is seeing, there must be acting.”

“Peace and non-violence do not mean non-action but that we are proactive in our love and compassion.”

“As a community we must demonstrate that peace is the way.”

“Mindfulness must be engaged.”

“Mindfulness is the awareness and transformation of not only our own suffering, but of the suffering around us.”